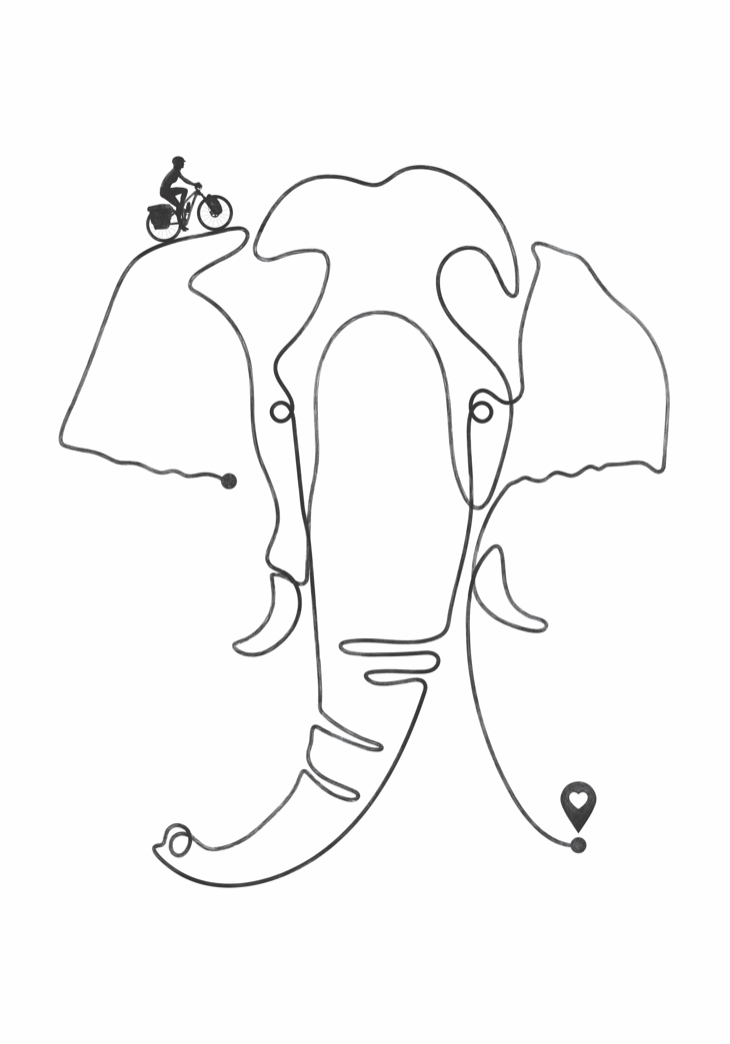

Under An Elephant’s Belly - from The Biggest Book of Yes,

an anthology of adventure stories. Published 2020.

The Biggest Book of Yes is a tome of 49 stories of adventure from 49 authors. Where the stories aren’t always about the outdoors. From driving a solar powered Tuk-Tuk across India to converting a bus, from thru-hiking to home schooling, the book brings you adventure in all its glorious forms. There’s a story for everyone in The Biggest Book of Yes.

The chapter Esther contributed was done so with the aim of raising awareness of the brutality Asian elephants in captivity are forced to endure and the critical situation they face, while sharing her uplifting experience of working as a volunteer at Elephant Nature Park in Thailand. It’s about how in the spring of 2018 she set off with her husband, David, to cycle across Central and Southeast Asia - without an iota of cycle touring experience between them. Heading east from Istanbul, over the following year they proved you can accomplish just about anything if you’re not in a hurry.

Just as their year on the bikes was coming to an end, one night – on not much more than a whim – they signed up to work as volunteers at Elephant Nature Park and in doing so, turned down one final road where they met a herd of elephants and a woman who changed the course of their lives.

Read the full story, ‘Under An Elephant’s Belly’ below.

Illustration Credit: Holly Doucette Design & Illustration.

Under An Elephant’s Belly

I’m standing on the upstairs balcony of the main house, a simple wooden structure surrounded by trees. I notice the way their branches reach towards the sky like long, contorted arms. Two elephants saunter past, their trunks swaying, and I experience the intoxicating pull that so many of us feel in the presence of these four-legged giants: a desire to be close whilst simultaneously awed by their power and size.

The sky and surrounding hills are thick with the smog caused by fires as nearby forest is cleared. It burns my eyes and sits in my throat. I feel a tightening sensation in my chest, as if my heart’s constricting, as I imagine the trail of death and destruction the fires are leaving in their wake. I force my mind away from the image and look towards the river that runs along one side of the property’s perimeter. I watch as the two elephants lower their large, rotund bodies into the flowing water and as they exhale and relax, so do I.

I’m looking for Faa Mai, the first elephant born at Elephant Nature Park (ENP). I’m holding a wooden carving of her in my hand – a surprise gift for David, my husband – but also a keepsake to remind us both of what can happen when you’re willing to, ‘Keep some room in your heart for the unimaginable’, as the late poet Mary Oliver once wrote.

I could never have imagined this.

I thought leaving everything that felt comfortable, familiar and safe in London almost a year ago to embark on a cross-continental cycling expedition had transported me beyond the limits of my imagination. Then it led us here, to working as volunteers with rescued elephants in Thailand.

To my left, a burst of movement from the trees grabs my attention. I turn to see Faa Mai running towards the house. I can’t help but laugh at the loose pile of corn stalks piled atop her head, the top ends fanned across her face like a fringe. I’ve learnt it’s not unusual for elephants to adorn themselves this way. Her chubby legs, not dissimilar to those of a toddler’s, pump up and down as she propels herself across the cracked earth, dry from a lack of rain.

On the platform below, day visitors jostle one another excitedly as a herd of elephants make their way towards the house and a rainbow buffet of fruit on offer. I look back at Faa Mai. It’s obvious from her expression that she’s determined to be first in line for the food.

Faa Mai is ten years old, no different from a child, and she endears herself to everyone she comes into contact with, animal and human alike. She’s curious, intelligent, playful and very social. She regularly leaves her mother and herd to pay visits with the elephants that have been rescued by ENP’s founder, Lek Chailert and her husband, Darrick Thomson. They’ve been rescuing captive service elephants ever since the sanctuary was founded in the 1990s. It’s since become a mix of hospice, rehabilitation centre, orphanage and most importantly, a safe and loving home for almost 100 elephants.

While Faa Mai will never be truly wild, knowing that her life won’t follow the same trajectory as many of the roughly 3,800 captive elephants in Thailand - not to mention the thousands more held captive throughout Asia - gives me reason enough to close my eyes, put a hand on my heart and send a prayer of thanks to the Universe. Faa Mai will never have her spirit cruelly broken in order for her to work as a captive service elephant.

In order to break an elephant’s spirit, it is tortured.

*

I desperately want to avert my eyes from the screen, but I steel myself not to. It’s our first full day at ENP and seeing this documentary is required viewing as volunteers. It’s scheduled early in the week for a reason: so we truly understand what captive service elephants - that is, any elephant working in the logging or tourism industry, or any elephant who provides entertainment or plays a part in religious activities - goes through.

What we learn is the most critical lesson of our entire volunteer experience.

We’re watching a baby elephant being put through Pajan, the barbaric process used to render a wild elephant docile, also called the ‘crush box’. I’m sickened by the gruesome scene playing out before us; the elephant stands in a cage, chained and roped and surrounded by a dozen or so men of various ages. It’s obviously distressed. It’s unable to move or lie down but it fights bravely against its restraints and I watch in horror as it’s beaten with chains, clubs and sticks and blood runs from its body, ears and feet as they’re stabbed repeatedly with hooks and nails.

I learn that it will be tortured this way, hour-after-hour, for up to ten days. It will also be deprived of food, water and sleep during this time in an effort to speed up the ‘crushing’ process.

I lean into David for comfort, which does nothing to stem the flood of tears I have no power to stop. I imagine how much that baby must be yearning for the comfort of its mother. It could be anywhere between just one and three years old. If captured in the wild then there’s a high chance the mother was killed, otherwise it was most likely conceived through forced mating - a common practice that’s tantamount to rape. Whatever the situation, after Pajan it will never be a baby elephant again.

Every single captive service elephant across the world has been through some form of Pajan.

The goal of Pajan is 100% submission.

*

I was aware that almost 100 African elephants lose their lives every day as a result of human-elephant conflict and poaching. I’d seen numerous gruesome images of their mutilated bodies. I’d go so far as to say I’d almost become desensitised to these images, much to my shame. The problem just felt too big and too far outside of my realm to help solve.

It’s far too easy to turn away when a problem feels overwhelming or impossible to make a difference. It’s easier still to simply ignore an issue when it’s difficult to comprehend the impact because you can’t actually feel it, when it’s someone else’s problem that you’re watching on TV from the comfort of your couch.

However, travelling by bike brought me face-to-face with blackened countryside, ravaged by fire and cleared for agriculture and development. I traversed through hundreds of kilometres of drought-stricken land, the soil overexploited through human activities such as grazing and growing. In gorgeous locations so remote that the only thing connecting us with the outside world was a satellite phone, I opened my tent on the side of a mountain one morning to witness a spectacular sunrise, and much to my distress, wet wipes fluttering past in the breeze.

Each experience led to many dark moments questioning if there’s any place on Earth left untainted by humans. I was no longer watching ‘someone else’s problem’ from afar. Instead, cycling had immersed me in the truly bleak reality of some of the issues faced by this beautiful planet we call home.

Then cycling brought me, quite literally, face-to-face with Asian elephants.

I stand amongst them and I hear their personal stories. I cry and I rage against what they’re forced to endure and how they’re exploited for human entertainment and pleasure.

Simultaneously I learn, no – I witness – how they’re sentient, empathetic beings, with an emotional IQ not far removed from our own. I watch an able-bodied elephant use its trunk to assist one who’s disabled, elephants who can see being the ‘eyes’ for elephants who are blind, how mothers and nannies rush to help the babies climb up steep river banks and a fortnight after leaving ENP, I sob all over my laptop while watching a video which shows the body of an elephant who has died of old age laid out for burial. It’s not his mother, yet one of the babies has draped himself across the dead elephant in grief. The herd surrounds them both and they mourn together in chorus. Their cries echo across the surrounding hills and into the deepest recess of my heart. Their sorrow is palpable.

*

I’ve not been at ENP long when I realise how horribly ignorant I am. I’m shocked to learn of the Asian elephant’s near-extinction; there are only 45,000 left, but I’m even more shocked to learn of the horrific lives one-third of those elephants live in captivity.

The cruelty doesn’t end with Pajan – it continues daily as they work as slaves, carrying tourists and unable to drink, forage, play or socialise the way a wild elephant would. Brutally controlled by the prodding of a bull hook or a nail discreetly pressed into their skull. Despite their imposing size, they’re not physiologically designed to carry weight, which causes pain. There’s no acceptable reason for riding an elephant, but ignorant tourists create the demand.

Once your eyes are opened you can’t not see the cruelty: elephants forced to be ‘painters’, or to perform demeaning tricks in circuses or shows, or on busy city streets. What torture that must be for these magnificent, wild beings. And those elephants that stand so patiently outside of temples? They’re often held in place with spiked shackles that eat into their flesh if they move. While festivals and religious ceremonies may look like the perfect photo opportunity, consider how that pretty procession of elephants are being made to walk for miles on a burning hot tar road, often transported from one event to another, as if a single procession with noisy crowds wasn’t terrifying enough for a creature whose home is in the forest. So many of these activities appear harmless, but there’s a dark side to animal tourism that far too many of us simply aren’t aware of.

It occurs to me that while I don’t play a role in supporting any of these activities, by doing or saying nothing, I’m effectively refusing to play a role in the solution.

*

A day that was remarkably clear of smog and has turned into one of those beautiful evenings when the sky turns an increasingly deeper shade of blue as the sun begins to set. Sultry cedars swing lazily in the breeze. David and I are sitting amongst our fellow volunteers on lounge chairs scattered along the balcony of the main house. I look at their faces and think about how I’m going to miss these new friends. They’ve come from all over the world and everyone’s lives are different, but we’ve bonded over this shared experience.

It’s such an odd thing to meet strangers and connect over so much suffering, but there’s so much beauty and hope here, too. We’ve held one another and we’ve cried, but we’ve also laughed as we’ve worked side-by-side, and willingly shared intimate details of our lives in a short space of time. Perhaps learning each of the elephants’ personal stories has made us less reticent about sharing our own.

I ponder the way humans are drawn to one another while everyone else remains unusually quiet, either reading or writing. I’m vaguely conscious of a sprinkler coming to life and its clackety-clack adding to the sounds of an evening unfolding. What we’re all hoping to hear is the dinner bell, except we’re suddenly treated to another, far more appealing sound: the trumpeting of an elephant.

I leap to my feet. An elephant’s trumpeting never fails to evoke a soaring feeling in me. It’s the sound of the wild and I feel my own wild within being summoned too.

The others aren’t far behind me, we’re all eager for a front row view. We’ve been here long enough now to know who plays this particular solo. Chana is a nine-year old orphan who, after being put through Pajan, was forced to work performing circus-style tricks and begging for money from tourists on the streets. It’s unknown how the injury occurred, but her leg was broken in two places and left untreated. As Chana was unable to work, she was of no further use to her owner.

Chana’s injuries are still too serious for her to be able to roam and play with the other elephants without the risk of being further injured by accident. So, she stays in a separate area within the sanctuary during the day. However, when the other elephants are bedded down in their sleeping enclosures for the night, Chana is given the run of the park.

We watch with delight as she runs as best she can towards a dirt pile where she sits on her bottom before slumping with a flop onto her side, causing fine dust to rise and envelope her in a red cloud. Minutes later she’s working hard to get back on her feet, but you can see the determination in her eyes and soon she’s lumbering by and trumpeting away again. She’s such a joyful sight and Chana’s trumpeting is a way of expressing her excitement at being free to explore and play. I can’t help but think of my three little nieces who start shrieking the moment they get home from school and are finally allowed to go outside and let off steam. Chana’s excitement is no different.

Until my time at ENP I had no idea how playful and social elephants are, how human-like. I’ve passed many happy hours watching them swim and play together in the river, often plunging at speed into deep channels of water. Who knew an elephant could completely disappear right in front of your eyes? That’s until trunks appear above the surface like snorkels, allowing them to remain fully immersed for as long as they wish. It’s impossible not to get the giggles as they splash about. Due to their sensitive skin, they take mud baths to protect it, but a large amount of comedy-like wrestling also takes place in those baths. If you’ve never seen a bunch of elephants covered in mud and wrestling, I’m not sure you’ve really lived.

Gingerly following Chana is Kabu, a 29-year old female elephant. Chana’s story is sad enough, but Kabu’s story is the one that keeps me awake at night, tears pouring down my face as I try to bend my mind around the complexity of the Asian elephant’s predicament. This isn’t a black and white issue based only on cruelty and greed – although it is tourists who drive the abhorrent demand to be carried and entertained by elephants. However, there are cultural and long-held traditions to consider and many elephant owners have families to provide for and very few options. To believe the problems - and therefore the solutions - are simple is a naïve way of thinking that risks creating further barriers, rather than breaking them down. However, I still struggle to comprehend how the human race can be so callous to animals, how we’re so quick to discredit their pain and suffering simply because they’re just that, an animal. And there’s something I find particularly pitiful about how we wield our power over elephants.

Kabu came to ENP after she was crippled following a logging injury. Logging was banned in Thailand in 1989 but still takes place illegally or in border areas. Elephants doing this work are at risk of having their legs snapped under the weight of chains or logs and many are forced to continue working well before their injuries have healed. But not only was Kabu crippled, she had two babies torn away from her and put through Pajan. As is often the case when an elephant is forced to live a life of fear, hardship and misery, Kabu was so emotionally traumatised when she arrived at ENP that she shunned other elephants and preferred to be left alone.

That is, until Chana arrived and Kabu immediately adopted her.

A motherless baby and a mother who had her children torn away from her, both elephants were psychologically and physically traumatised but have formed a bond that will last their lifetimes. It’s a critical bond that also plays a key role in helping them to heal. Elephants are highly sensitive, social, loving beings. They recognise and will run to greet one another and even hug with their trunks.

An elephant that prefers to be left alone has forgotten how to be an elephant.

As I learn the ways of a wild elephant, it’s excruciatingly obvious how torturous it must be not to be free to roam far and wide, foraging throughout the day led by instinct and memories. How hydrating via a trough and hose is a far cry from being able to suck water when needed from a cool river, or a watering hole. How maddening it must be not to be able to protect sensitive skin with dust or mud. Living instead, if it can even be called living, constrained in shackles for decades, forced to exist according to a human’s wants and way of life.

Yet what inflicts the deepest wounds of all is how elephants’ complex emotional lives are virtually held in contempt, even used against them to further break their spirit. Just like us they crave connection and love but their social structures are even more complex. In the wild a female elephant will spend its whole life living in a tightly knit family group, led by the matriarch. They care for and protect one another, and work together to raise one another’s babies. We could learn so much from their example.

While humans consciously seek to form deep bonds outside of family, an elephant’s desire to be with theirs is deeply innate. Take that capability away from them and tear their families apart and you’ve removed an intrinsic part of what makes an elephant an elephant.

Kabu was fortunate. Many elephants never recover from the trauma of being torn apart from their loved ones.

*

“I don’t want to leave,” says David, looking at me intensely.

It’s evening and we’re back in our room getting ready to turn in for the night. We’ve only been at ENP a few days and the plan had been to volunteer for seven then make our way to and through Myanmar by bike, before concluding our travels. If we stay any longer, that plan will become obsolete.

“Me neither,” I reply.

We stand facing one another for a moment as the ceiling fan hums above us and colourful geckos crawl up the walls. I’m holding a pair of earrings in the palm of one hand, two gold spheres engraved with Sanskrit. I bring them up to my face and study them for a moment, as if I’m searching for a clue.

“What do you want to do?” I finally ask, confident I already know the answer.

I’m not the only one who’s been affected by the elephants. In the fifteen years we’ve been together, I’ve only seen David cry on a couple of occasions. As my gentle husband has interacted with these equally gentle giants, I’ve seen tears dampen his cheeks several times. I’m watching the person I love the most change in positive, powerful ways right in front of my eyes, simply from being in their presence.

“Let’s see if we can stay for longer,” David suggests.

When David and I wobbled out of Istanbul almost a year ago, we didn’t entirely know what we were doing. I’d suggested we cycle a route we’d originally planned to drive, despite not having an iota of cycle touring experience between us. We’d frequently giggled together about the ambitious, cross-continental path we’d chosen for our first expedition. Yet the trip had far exceeded any expectations either of us may have had, and we’d adapted easily and quickly to life on the road.

It would have been so easy to keep going beyond the year we’d planned to spend travelling, but David had recently accepted a job offer in London. Yet it’s no secret I was hoping we wouldn’t return to the city we’d left, at least not to live.

As I step out of my clothes I contemplate the end of our journey and I know I’m not the same person who left London all those months ago. I’ve changed in ways I could never have anticipated and I want the life I live there to change too. I’d been so sure that by the end of this trip I’d have a clear sense of direction, but I’m still not entirely sure what I’m going to do in the next chapter of my life.

However, despite my reluctance to return, I can’t shake the feeling that our journey was always going to lead us to ENP and that we were always going to return to London. I can feel the elephants altering the course of my life, even if I don’t quite know how.

*

“Welcome to my office!” says Lek with a giggle as I get down on my hands and knees and crawl underneath Faa Mai’s belly to sit with her. I’m having a serious ‘pinch me’ moment. I didn’t expect to be sitting under an elephant with a world-renowned Asian elephant conservationist today – or any day, for that matter.

It’s the first time I’ve met Lek. She recently returned from an educational tour and has come to see Faa Mai and one of the herds. She has a close relationship with every animal she rescues and yet it’s her bond with Faa Mai that’s the strongest. Faa Mai’s chubby legs couldn’t move fast enough when she spotted Lek, the elephant’s reaction is reminiscent of that of a child’s who’s just seen an ice cream truck. There’s definitely a moment when I’m convinced we’re both about to be devoured. But Faa Mai comes to a stop, ears flapping with pleasure and pushes Lek gently into a crouch so she can fit between her front legs, as if Lek were a baby elephant in Faa Mai’s care.

Which is how I come to be sitting opposite this tiny Thai woman and the formidable driving force behind so many of the projects we’ve been learning about. From rescuing captive service elephants to running educational programmes and helping elephant-related tourism attractions and camps convert to an ethical business model, and so much more.

I’m surprised when Lek shares her frustrations with me, a stranger. But she’s been doing this work for decades and has witnessed so much cruelty and is keen to educate others. I wonder how much she must suffer; it must break her heart repeatedly, knowing that for every elephant she helps, there are far more she must leave behind.

Lek shares her dreams, too. Of semi-wild projects that allow a number of elephants to live with minimal human intrusion, even though that’s sadly not what most tourists want. Lek knows that even ethical businesses aren’t the perfect solution for the elephants, but they can be a way to educate and therefore a stepping-stone to something better.

And without tourism, businesses risk running out of money to provide even minimal care for elephants. At the time of writing, all elephant-related businesses in Thailand are closed due to COVID19 and at least 1000 elephants are at risk of starving to death. The forest may be the elephant’s home, but the ugly reality is that there’s not enough forest left to sustain the wild population, let alone a large number of elephants that have previously been held captive.

What strikes me the most about our conversation though is that despite everything Lek’s seen, everything she’s been required to sacrifice and for all the work that still needs to be done, there’s no judgement of others, no shaming. Lek tells me she believes that true change comes when we lead by example and show compassion and love. She’s a living example of how successful that approach can be. As she talks, I experience a moment of realisation. The elephants may have started to change the course of my life, but meeting Lek was the final push I didn’t even know I needed.

*

The herd approaches and as we stand to greet them the elephants eagerly reach for Lek, reminding me of when I return to my family after being away. Everyone wants to hug and be hugged at once and there’s that wonderful feeling when one embrace ends and another immediately begins. Only this time arms are trunks.

It’s obvious Faa Mai isn’t the only one who’s devoted to her. The herd express their delight at Lek’s presence with low, guttural sounds, nuzzling her hair, face and body with their trunks, smearing her face and clothes with red mud from the baths they’d been playing in moments earlier. I watch, entranced, as Lek turns towards the river and as she does so, Faa Mai winds her trunk gently around Lek’s wrist and they walk side-by-side. It’s such a natural, almost intimate movement that makes me think of a child slipping her hand unthinkingly into her mother’s.

The more time we spend with the elephants, the more at ease they become in our presence. Soon they begin to nuzzle our hair, faces and bodies too. Lek takes my hand and directs me to stand right in front of Faa Mai - I’m literally tucked under her chin - and then she verbally guides me to place a hand on either side of Faa Mai’s head and up behind her ears. I run my palms across thick, furrowed skin, which is surprisingly soft in this shrouded place, out of sight from the sun. I close my eyes and I breathe her in.

After a while I step back so I can look into Faa Mai’s eyes. She lifts her trunk and gently caresses my face and I’m so choked with emotion that all I can do is stand there, tears streaming down my grubby cheeks. To stand eye-to-eye with an elephant at peace is to feel its extraordinary healing power.

As we walk back towards the house, I feel profoundly affected. I’m astounded by how these magnificent animals have been so horribly abused by humans, and yet they’re so willing to forgive the unforgivable and share their deep sense of loyalty for family with the people who love them.

As for Lek, I’m in awe of the incredible work she does but I’m even more in awe of who she is as a person and how she goes about that work. The elephants have shown me what I want to do next, but it’s Lek who’s shown me how to do it. I needed to see activism and advocacy conducted in a way that reflects my values. I can see my next step.

*

Since returning to London David has often joked that, “Rather than cycling across the biggest land mass on the planet, all I really needed to do to get a little perspective was to hug an elephant”. But we both know that’s not true. We wouldn’t have been the same people without all the experiences we’d had as we unknowingly cycled towards ENP.

We left everything that felt comfortable, familiar and safe behind and in doing so, we expanded our perception of how much more we’re capable of, as a couple, but as individuals too.

I needed to wobble out of Istanbul on my bike with no idea about what I was doing, to leap into the unknown, in order to truly understand that you don’t need to have all the answers before you start something. You just have to take the first step.

Yet I spent far more time on that journey than was necessary trying to figure out what I was going to do once it was over. What I learnt is that answers rarely arrive the way you may expect or even want them to. I didn’t expect to reach the end of our trip with no clear sense of direction, only to take a final road that literally led me to a herd of elephants and a woman who would change the course of my life. I didn’t expect to become an activist and advocate for elephant conservation.

Now when I talk about elephant conservation people ask, “Why elephants? There are so many causes that could use your attention,” and that’s true. But in a world that constantly asks, “What’s your why?” I don’t believe we always need one. Sometimes you feel a calling so strong you respond without question. I still can’t explain why I suggested we cycle a route we’d originally planned to drive. I just know it’s what my heart wanted.

It’s no secret that I was hoping I wouldn’t return to London, at least not to live. Yet it’s the elephants that made returning so much easier and I believe it’s exactly where I’m meant to be, for now. I’m using my voice to stand up for what I believe in and I do so following Lek’s example. I also know now that a problem is never too big or too far away to help solve.

Take the leap, take your time and be willing to believe that, ‘What you are seeking is seeking you’, as Rumi says. And always, always keep some room in your heart for the unimaginable.

***

Read about our cross-continental cycling expedition from Turkey to Thailand

and the birth of Act Big Live Small in a beautiful essay by David here.